In 2021, the WTO appointed a new DirectorGeneral, Dr Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, the first African and the first woman to lead the organization. With this new leadership and vision comes a renewed emphasis on the role that trade can play in improving livelihoods, creating opportunities for full employment, and achieving sustainable development in line with the objectives outlined in the Marrakesh Agreement Establishing the WTO and the Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development.

This commitment to making trade and the work of the WTO centred on people is one the main reasons why the work of the organization has been devoted to building back a stronger and more inclusive global economy, and reviving progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). It has also been strongly reflected in the work done by the Director General to improve access to the COVID-19 vaccine and has been translated into concrete steps to ramp up and diversify production in developing countries, particularly on the African continent.

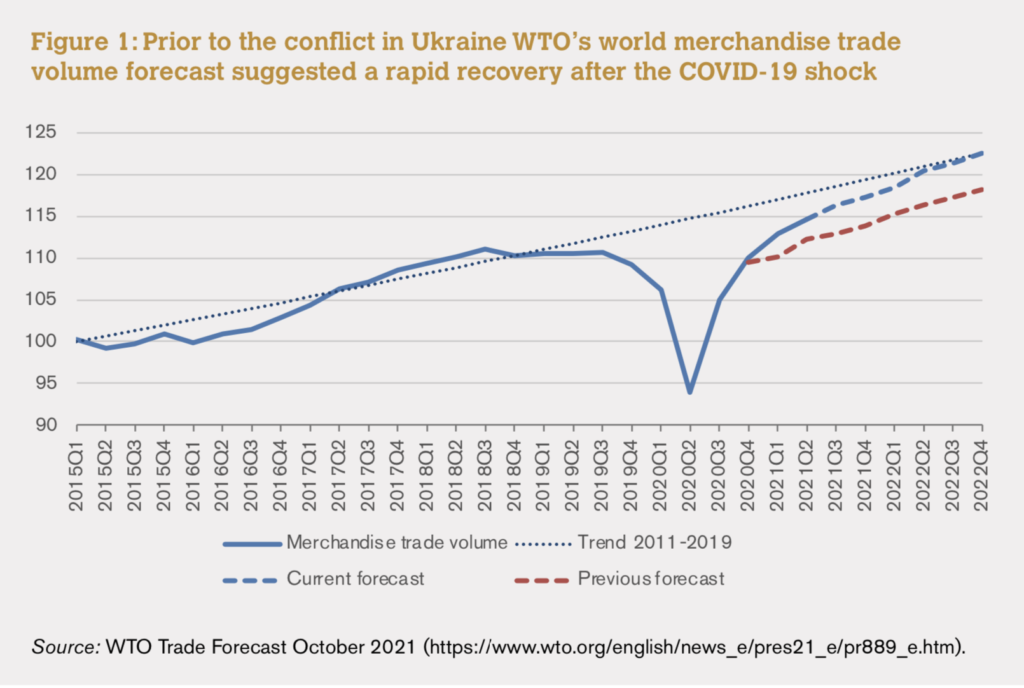

The COVID-19 pandemic has put massive stress on the world trading system. This started with lockdowns, which generated a severe reduction in economic activity, leading to a temporary collapse of global trade. In 2020, the value of global trade in goods and services in nominal dollar terms fell by 9.6 per cent, while global GDP fell by 3.3 per cent, in the most severe recession since World War II. But a quick recovery of merchandise trade flows followed in 2021. The WTO predicted a growth of 10.8 per cent of world merchandise trade volumes in 2021, followed by a 4.7 per cent rise in 2022, as shown in Figure 1. However, following the Ukraine conflict, the WTO Secretariat revised its trade forecast for 2022 in its report assessing the impact of the war, released in April 2022 and titled The crisis in Ukraine: Implications of the war for global trade and development.1 Using a global economic simulation model, the WTO now forecasts that the conflict and related policies could knock 0.7-1.3 percentage points off global GDP growth, bringing it to somewhere between 3.1 and 3.7 per cent. Using the same simulation model, global trade growth this year could be cut almost in half, from the 4.7 per cent forecasted in October 2021 to between 2.4 per cent and 3 per cent.

Ukraine and Russia taken together may account for barely 2 per cent of global GDP, and 2.5 per cent of merchandise exports, but they are key suppliers of food, energy, fertilizers and certain metals. As a result, the economic shocks emanating from the Black Sea region, starting with higher food and energy prices, have implications for the lives and livelihoods of people around the world and for the global food and nutrition security situation.

Considering this situation, the UN Secretary-General set up a three-tier steering committee at the levels of heads of government, heads of international organizations, and technical experts to examine the issue of surging energy and food prices, assess the impact on developing countries and formulate recommendations. The WTO has been invited to join this committee and is expected to play a key role in finding solutions to this looming crisis that threatens to roll back progress in achieving SDG 2 on zero hunger, but also SDG 1 on poverty. The WTO Director-General, as well as the heads of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Bank Group (WBG) and World Food Programme (WFP) also issued a joint statement in April 2022 calling for urgent food coordination on food security.

Prior to the conflict in Ukraine, a strong rebound in global trade and the increased demand for consumer durable goods at the expense of services, such as tourism, put some supply chains and the global shipping system under stress generating customs and logistic bottlenecks and increasing trade costs uncertainty. The unfolding tragedy in Ukraine is adding to supply chain woes. While the full implications for global supply networks will take time to become clear, there have been immediate impacts on global food security, with sharp price increases for grains, oilseeds and vegetable oils, and fertilizers, as well as energy.

In the near term, international cooperation on trade will also be crucial to minimize the impact of supply crunches in key commodities for which prices are already high by historical standards, and to keep international markets functioning smoothly. Only through coordination can governments avoid a repeat of the cascading export restrictions that exacerbated price increases in the food price crisis of 2008 to 2010.

In the long term, supply resilience will be best served by deeper and more diverse international markets anchored in open and predictable rules. Concentrating sourcing and production at home, while understandable, could also create new vulnerabilities and may not be the best risk management strategy.