- Equity markets did not consistently react immediately after climate-related political or regulatory events. And, often, stock prices moved in the opposite direction of what was expected.

- Some of this lack of consistent reaction may be due to the protracted nature of the political decision-making processes. Markets may price in policy changes prior to their final adoption.

- When looking at stock-price returns over longer periods, we found that more carbon-efficient companies’ outperformance developed slowly over time and accelerated during the past two years.

Have climate risks been reflected in equity prices? We find that the timeframe used in evaluating the impact of events on market prices is critical. In previous research, we explained that there are two types of risk drivers we can use to detect a relationship between events and stock price: ”event risk” refers to risks that are more immediately priced in by investors while ”erosion risks” tend to play out over longer time periods. In this blog post, we explore how equity markets have reacted to climate transition risks.

The transition toward a net-zero economy is not a smooth process. It is sprinkled with events that represent important leaps forward or (sometimes) significant setbacks. These events allow us to gauge how strongly market participants believe climate transition risk is transmitted to firms’ stock prices.

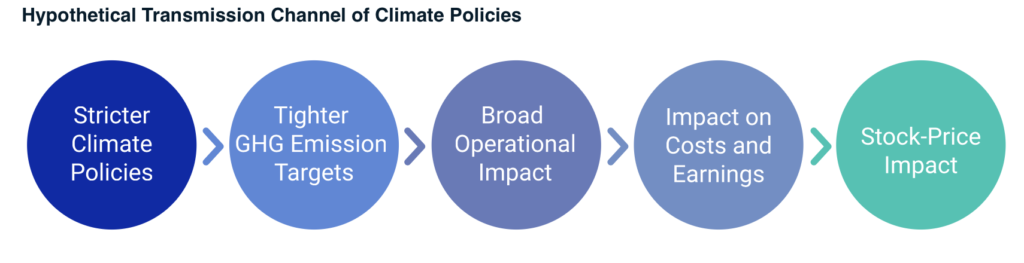

We have created a hypothetical transition channel of how changes in climate policies such as the 2015 Paris Agreement may be reflected in stock prices. For example, policymakers are expected to impose tighter limits on greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Such rules may lead to increased costs and reduced earnings for firms with less-carbon-efficient operations, which in turn may have an impact on their stock prices. Alternatively, more carbon-efficient firms may have a comparative cost advantage. Our model, illustrated below, explains how these stricter policies could be transmitted into equity prices.

Hypothetical Transmission Channel of Climate Policies

Testing for Event Risk

To test whether policy events had an immediate impact on stock prices, we studied key climate-related political or regulatory events that have occurred since 2015. We looked at the relationship between stock prices and companies’ climate transition risk profiles, to see how strongly the equity market priced in this transmission channel.

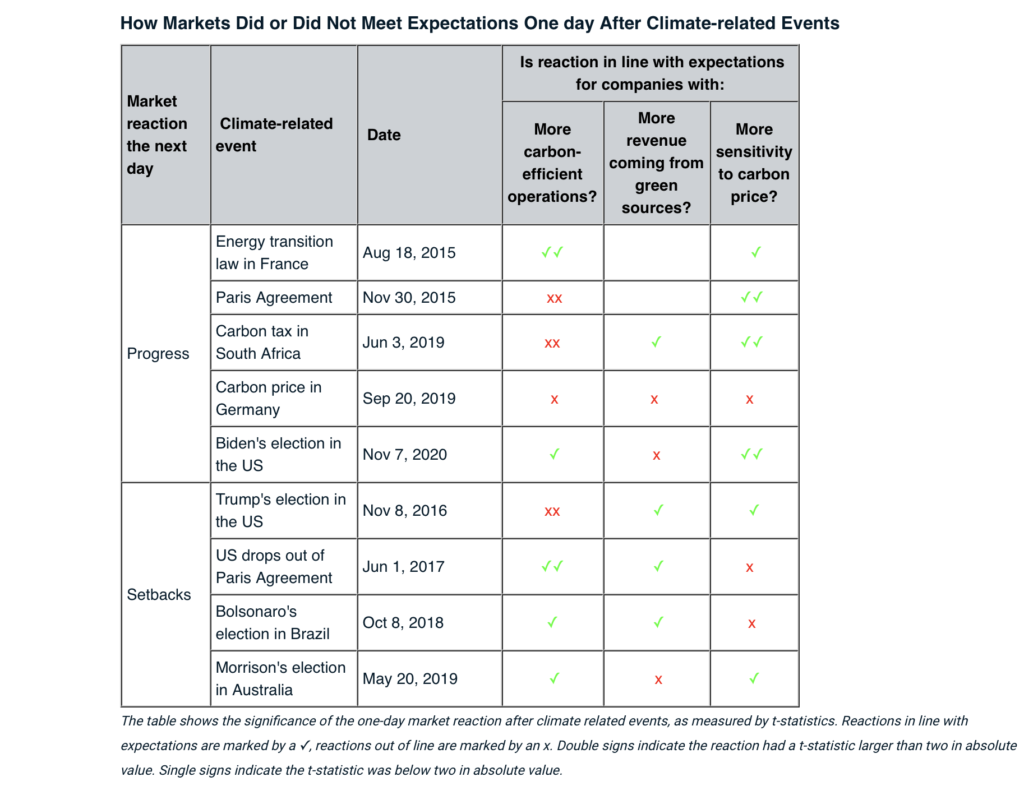

We selected nine events: five that could be considered ‘’progress’’ for the transition to a low-carbon economy and four that could be considered ‘’setbacks,’’ as shown in the exhibit below. We then looked at the stock returns over the trading day after the event to gauge the event risk in the short term. We were mostly interested in testing if greener companies (with less transition risk) outperformed after a “progress” event and underperformed following “setbacks” relative to their more carbon-intensive counterparts (with larger transition risk).

We proxied climate transition risk with three different variables: 1) carbon efficiency (the inverse of carbon-emission intensity), 2) share of green revenue (derived from alternative energy, energy efficiency and green buildings) and 3) carbon beta (stock-price sensitivity to European CO2 price movements).1 The framework also allowed us to quantify the statistical significance of our findings as can be seen in the exhibit below. 2

How Markets Did or Did Not Meet Expectations One day After Climate-related Events

The table shows the significance of the one-day market reaction after climate related events, as measured by t-statistics. Reactions in line with expectations are marked by a ✓, reactions out of line are marked by an x. Double signs indicate the reaction had a t-statistic larger than two in absolute value. Single signs indicate the t-statistic was below two in absolute value.

The data did not support the existence of a strong event-related transmission channel: For most events, the regression coefficients for the one-day period were not statistically significant nor were they consistent, i.e., the coefficients of different proxy variables for the same event did not always show the same signs. When we repeated the analysis for different time horizons, the average statistical significance did not increase, nor did consistency improve.

We need to temper our results: Some policy changes such as the Paris Agreement were not true “surprises” — that is, financial markets had ample time to price in expectations in the runup to the event and this could explain that immediate market reactions were muted. However, even Donald Trump’s election as president of the U.S. in 2016, which was arguably the most surprising event, immediately pushed up prices for more carbon-efficient companies — which was contrary to expectations. The results for the other variables were in the expected direction but were not significant.

Testing for Erosion Risk

If markets did not react immediately to climate policy changes, did they respond over time, suggesting the existence of erosion risk? To test for erosion risk, we used the MSCI Low Carbon Transition (LCT) Score to proxy companies’ exposure to climate transition risk. The LCT Score aggregates companies’ emissions across Scopes 1, 2 and 3 and also gives companies credit for their green-opportunity exposure and climate transition risk management.3

To assess how performance was affected by companies’ climate transition risk exposure, we included the LCT Score as an extra factor in a factor model4 and re-ran the regressions with this updated factor set over the past seven years (LCT Score data availability is limited to this period). The cumulative factor return associated with the LCT Score showed that companies with better transition risk profiles outperformed their riskier counterparts, after controlling for well-known equity risk and return factors (see the exhibit below).

Cumulative Low Carbon Transition Return

The relative outperformance of companies with better transition risk profiles mainly occurred during the last two years. The LCT return improved continuously over time, indicating that climate transition risk was more likely an erosion risk. This recent acceleration in performance may relate to the adoption of numerous climate-related policies at the regional level following the Paris Agreement, such as the Energy Transition Law in France, the carbon tax increase in Germany and the decrease in carbon allowances in the European trading scheme. Hence, the observed erosion in stock prices may simply reflect this ongoing regulatory process.

In short, we find that major climate-related events did not consistently meet our test as an event risk. Rather, they tended to play out in equity markets over longer time periods, consistent with our definition of erosion risk. It may help to consider these longer-term potential ramifications when evaluating companies’ climate transition risks.

More information visit www.msci.com